Yesterday, the Charlie Rose Show repeated interviews with comics Billy Eichner, Amy Pohler, Matt Besser, Ian Roberts, Matt Walsh, and Seth Meyers.

Yesterday, the Charlie Rose Show repeated interviews with comics Billy Eichner, Amy Pohler, Matt Besser, Ian Roberts, Matt Walsh, and Seth Meyers.

A couple of comments jumped out.

Matt Besser: “You don’t have to appeal to 30 million people anymore.”

Ian Roberts: [the stuff we do can be] “a little rougher, more radical, more experimental.”

So what does that mean for popular culture?

Samantha Bee has an answer (at least for Full Frontal):

“We just do the material that appeals to us, the sort of thing we want to see.”

Does this mark the beginning of the decline of TV as a mass medium? Is TV, at least comedy on TV, now the artist’s playground, a place where artists can satisfy their own creative agenda?

This would spell the end of that glassy, packaged, patronizing, anti-improvisational work that popular culture produced in the 1950s, the stuff that made comedy look like an airshow: “Here comes a joke, this is the joke, how great was that joke!”

But have we moved to the far extreme? Let’s call this the Samantha Bee extreme (hold all jokes to the end of the essay, please) where it’s all about the cultural producer, and no longer about the cultural consumer. At all. (There’s another possibility: that Ms. Bee has become tragically self indulgent, the Nic Pizzolatto of late night, and not long for that. I ignore this option.)

Seth Meyers had an answer. Audiences are getting smarter, he said. They have all the comedy ever recorded at their disposal on YouTube and they are “self educating.”

So, yes, apparently we are moving to the Samantha Bee extreme. Comedy producers and consumers are less different. They are growing closer. What a change this is! Comedians were once aliens who infiltrated the human community by manifesting on a standup stage, there to outrage and delight the sensibilities of people who really had no idea what comedy was or where it came from. Not now. Now more and more comedic producers and consumers make up one community.

This changes the comedian. She was once a tortured soul, torn between the popular success that came from “safe” comedy and the professional esteem that could only come from “daring” comedy. To use that airspace metaphor again (hold your applause to the end of the essay, please) comedy producers and consumers occupy the same airspace. The comics can just do better stunts.

It also changes the audience. They are no longer yokels at a country fair marveling at the ingenuity of these city slickers. (“Dang, how’d he do that!”) They are more likely to scrutinize the architecture of the joke, wondering if Samantha Bee “didn’t maybe put a little too much stress on the last word. I feel.” and then taking (or as Henry Jenkins would say, “poaching”) the joke for their own personal purposes, to make themselves funnier Saturday night at the bar.

This is all great news for some purposes. It’s good for Netflix, Hulu and Amazon. It’s good for Comedy Central, Funny or Die, and Seeso. It’s good for aspiring comics. Most of all, it’s good for contemporary culture, which gets funnier the more producers and consumers drive one another onwards and upwards. Call this the Apollo Theater effect, where the audience is so discerning, it forces entertainers to raise their game. (But now of course the effect is reciprocal.)

But it’s not all great news.

As two comedic worlds close, two cultural worlds tear apart.

As comedy producers and consumers get ever chummier, they take their leave of a large group of fellow Americans. I say, “fellow,” but of course that’s the point. As comedy gets better and pulls away, these Americans are less “fellow.” There are now millions of Americans who couldn’t find the funny in an Upright Citizens Brigade’s routine if their lives depended on it. They can’t actually see the point of it. And there are few things quite as alienating as this. You look a fool. You feel a fool.

There are two choices when this happens. You can accuse yourself of being witless and wanting. Or you can attack the person who has threatened you with this judgement, and call them an elite bent on taking your culture away from you. The only way to escape the “fool” judgement is to turn it on someone else.

And that’s where politicians like Donald Trump come in. And not just Trump, but an entire industry of pundits, experts, talk show hosts, religious leaders and other politicians have seized upon the “culture wars” as an opportunity to fan the flames of unrest, to mobilize dissent, to coax dollars out of pockets.

That’s where we are. Driven by technological innovations and cultural ones, there is now a dynamic driving groups of Americans apart, destroying shared assumptions, and putting at risk the hope that an always heterogeneous America can remain, in the words of Alan Wolfe, one nation after all.

This is not an accusation. There’s no obvious enemy. And there’s no obvious answer. No party, ideology, or interest can put Humpty Dumpty back together again. We may self correct. We may not. But chances are slim that this cultural divide will make no difference, not as long as certain interests keep hammering away at it.

But it is a confession. I wrote a book in the late 1980s called Plenitude in which I argued that the coming cultural diversity would be a good thing and that we would survive it without descending into a tower of babel or a world of conflicting assumptions. And now it’s beginning to look like I was wrong.

You can hear something tearing.

Like this:

Like Loading...

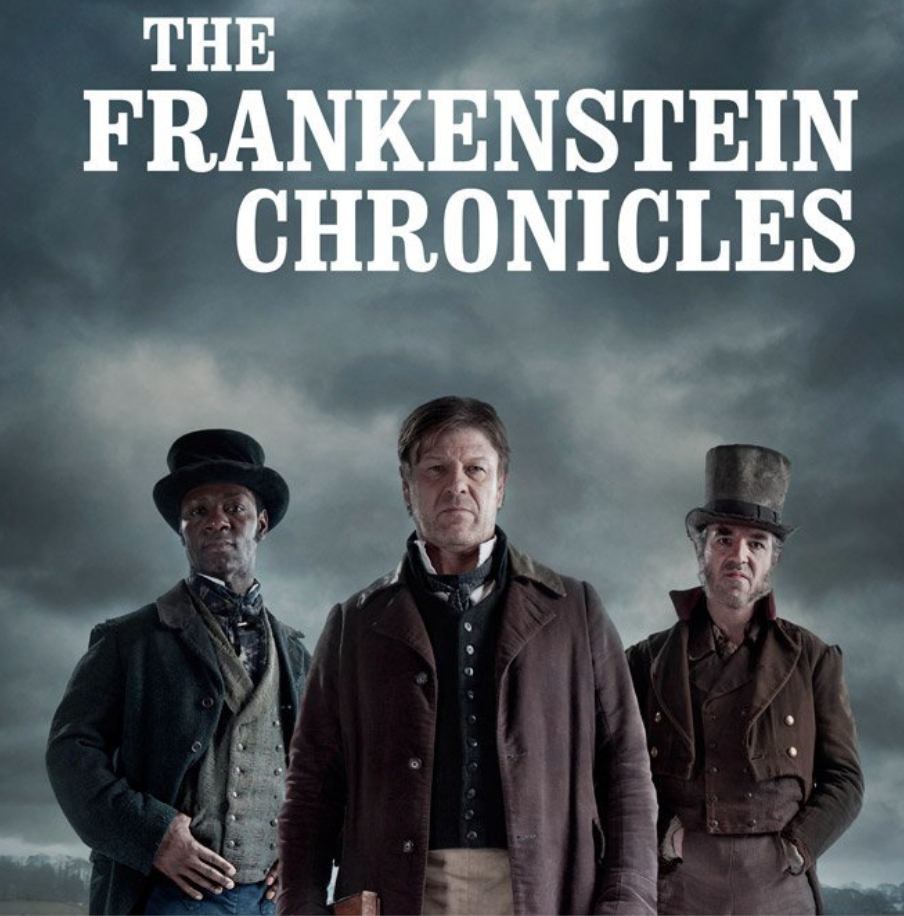

The thing that strikes you about The Frankenstein Chronicles is how gruesome it is.

The thing that strikes you about The Frankenstein Chronicles is how gruesome it is. Tom Friedman was interviewed by Al Hunt on Charlie Rose Tuesday night. He was pitching his new book: Thank you for being late: An optimist’s guide to thriving in the age of accelerations. And he offered, as he always does, a modular understanding of the world.

Tom Friedman was interviewed by Al Hunt on Charlie Rose Tuesday night. He was pitching his new book: Thank you for being late: An optimist’s guide to thriving in the age of accelerations. And he offered, as he always does, a modular understanding of the world. Jason Lynch

Jason Lynch  Yesterday, the Charlie Rose Show repeated interviews with comics Billy Eichner, Amy Pohler, Matt Besser, Ian Roberts, Matt Walsh, and Seth Meyers.

Yesterday, the Charlie Rose Show repeated interviews with comics Billy Eichner, Amy Pohler, Matt Besser, Ian Roberts, Matt Walsh, and Seth Meyers.

The Grinder is a show from FOX about a TV actor (Rob Lowe as “Dean”) who leaves his hit series, a courtroom drama, to spend some time in the “slow lane.” He wants to make contact with “real life,” to break away from the insincerities of Hollywood and the falsehoods of a celebrity culture.

The Grinder is a show from FOX about a TV actor (Rob Lowe as “Dean”) who leaves his hit series, a courtroom drama, to spend some time in the “slow lane.” He wants to make contact with “real life,” to break away from the insincerities of Hollywood and the falsehoods of a celebrity culture.