[This post first published on Medium March 16, 2018]

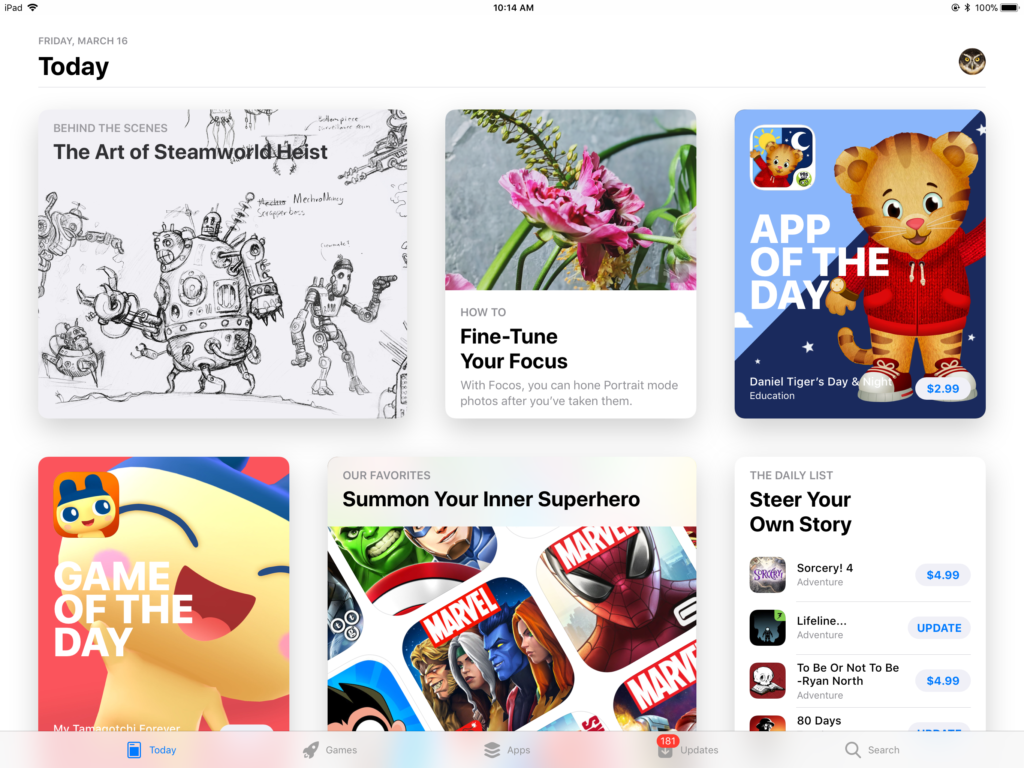

I was looking at the iPad app store this morning and noticed in the upper left hand corner The Art of the Steamworld Heist, offered there as a “behind the scenes” tour, and I thought.

“Oh, ok, this is how we do it now.”

This is how we do marketing and design now that the consumer is less the passive recipient of culture and more and more an active creator.

The “ad” for Steamworld Heist breaks all the old rules of marketing and design. It does not inform us of the game. It does not try to wow or pitch us. It does not state the value proposition. It does not engage in selling of any kind. There is almost no persuasion here. This ad merely say, “Hey, you might like to see how we made this game. Have a look.”

A lot of marketing and design still hews to the old model. We craft a product or service. And then we craft the brand. And we almost always do this in a closed room.

There was nothing transparent about this marketing and design. In fact, we work hard to keep it secret.

This old model presumes an active meaning maker on the producer side. On the consumer side? Not so much. We assumed the consumer was pretty much just sitting there in front of the TV, working hard to stay abreast of the plotting complexities of The Rockford Files, to say nothing of the terrible mysteries of that great fixture of American TV, the car chase.

But not so fast. I think this view of the consumer was largely a myth created for us by the Frankfurt school, that wrecking crew who declared war on popular culture and, by an unholy alliance with academics and intellectuals (rarely the same thing), conspired to prevent a post-war American culture from ever grasping that it was a culture. The consumer was always more active than the Frankfurt school allowed.

And these consumers have grown ever more so. And now they are very active indeed. It began with what Henry Jenkins called “poaching.” Consumers would steal ideas from popular culture and repurpose them. Fanfic, as we know thanks to the work of Abigail De Kosnik at Berkeley, was just the beginning. We see a new order of participation. Things scale up until a change in degree became a change in kind, and the consumer must now be reckoned as producer in his and her own right. (I expect Henry Jenkins might agree to this. His seminal Textual Poachers was 25 years ago.)

So here we are. The consumer is now a producer. And we have struggled to adjust in a variety of ways. But these efforts have been a little ad hoc-ish, I think. The more sensible, the more revolutionary gesture is to stop making meanings in secret. It is to begin to make our meanings under glass. (And of course to bring the consumer in the creative process, as I argue here.)

I believe someone will object, “But what if the competition sees.” So what? Anyone with half a brain can reverse engineer the design, the PR campaign, the product, the ad. In this sense, we are always transparent…at least entre nous. So an external transparency does not give the competition an advantage.

The way to speak to the consumer is as fellow making makers who find us most interesting when we share our creativity activities with them, when we are transparent about what we think we are trying to do.

Everyone is a culture creative now. We take a professional curiosity in one another’s work. Let’s invite the consumer backstage and let them see what we as designers, marketers, and branders thinking.

In short, we want to act more like the makers of Steampunk Heist. Let’s stop trying to trick, wow, impress or persuade. Who’s buying that? Transparency may be one of our last hopes of making contact.