A couple of days ago, I posted this question:

1) Why is Gill Sans winning out over Helvetica? (If it is, and, come on, it is.) Long the visual language of public institutions in the UK (the subway, especially), it looked until recently (to me at least) a little out of touch. But now it seems to be to have all the punchy clarity of the sans-serif regime without giving away the ability to evoke something bigger than the message at hand.

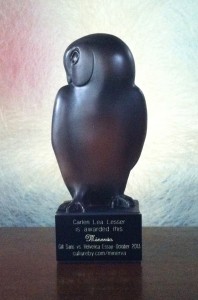

I invited people to submit answers, promising a Minerva to the best essay.

The results are in and the winner is Carlen Lea Lesser. Her answer is below.

Understanding the Return of Gill Sans

by Carlen Lea Lesser

Each era seems to have a font or fonts that define it, and from then on that font carries the weight of history and all the cultural associations that go along with it. While Helvetica seems to have been the font of choice since it’s arrival on the scene in the 1950s, recent years have seen the resurgence of Gill Sans. While it may take a long time for Gill Sans to over take Helvetica — if it ever does — there does seem to be a clear trend. One way to understand interplay between these two fonts is to use the generational/socio-cultural theories of Strauss and Howe. These two historians mapped a pattern of interconnected generational (Generations) and socio-cultural (Turnings) cycles that repeat every 80-100 years and tracked back through all of American history and back through much of British history. By analyzing the times these fonts appeared and re-appeared through the lens of the four turnings, we can see that there are clear cultural reasons behind Gill Sans gaining new popularity.

Helvetica comes out of the late 1950s the end of an era of post-war prosperity and confidence; smack in the middle of the “American High” period in the parlance of Strauss and Howe. Despite being created in Switzerland, it screens the 1950s vision of modern and clean. The lines are strong, bold and clear — the ambivalence and confusion of the Great Depression and WWII are gone. One of the interesting characteristics of Helvetica is its relationship to the Bauhaus movement. Helvetica was designed to take the emotion out of type. It was seen as a “neutral” typeface that would not add any additional mean or emotions. It presents itself as strong, clear, and bold. It is a font that has the promise of this exact moment being right and true.

It is both surprising and unsurprising that Helvetica held on through the 1960s and all the way into the 2000s. No one ever really wants to let go of a High Period, especially those who were raised in one like the Baby Boomers. High Periods, like the idyllic 1950s and early-1960s of the Boomers’ childhood, are times of great security and public confidence in institutions, and lacking in individualism. In the Awakening of the 1960-1970s, Helvetica would have represented a calm center in the storm for those tossed about by the counter-culture revolution. It was the font of IBM, American Airlines, and Bell Atlantic; solid, stable companies that represented the best of America. As we moved to the Unraveling of the 1980s-1990s, those same people who needed the stability of Helvetica in the counter-culture of 1960s needed it even more, and the former Hippies turned into the Yuppies of the 1980s. Needless to say the promise of economic growth of IBM, Mattel, and General Motors was appealing to the Yuppies of the 1980s.

Then there is Gill Sans, a product of the late 1920s England. The font it a derivative of “humanist” sans-serif category of san-serif fonts, but with more line variation and legibility of many sans-serifs. It’s considered to be the most “calligraphic” of the sans-serif, which I take to mean the one you can that most lets the humanity through. It’s a font that seems to have one foot in the past and one foot in the future. It promises a future more interesting than clean, clear, and strong. It moves away from the curly-cued serifs of the Art Nouveau era and foreshadows the “Great Gatsby” era deco lines that would follow in the years to come. But it doesn’t really evoke either era. Gill Sans is really a font about hope — hope of moving out of the Crisis of the Great Depression and into that beautiful American High period.

While designed just before the Great Depression, Gill Sans really hit its peak when Penguin books adopted it for its cover fonts in 1935. By most measures the USA and the world began to recover from the Depression around 1933. It was hardly a boom time, but signs of improvement were beginning. 1935 was the height of the Art Deco era, and Gill Sans — a font developed just a few years after the Art Deco aesthetic was introduced to the world became the font of choice for what was to become of the world’s biggest publishers. Edward Tufte puts it best when he describes it is a classic and elegant looking font. It is a font that evokes the best of what the Art Deco movement was about: faith in social and technological progress (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_Deco). A believe that the Crisis will end and not only will everything be okay again — but better than before.

While Helvetica may have persisted because it subconsciously reminded Baby Boomers of their childhood in the 1950s, a time idealized as having been when all was right and good with the world, Gill Sans is a font of faith in progress. Which do we really need right now? As we are in the heart of the current Crisis period, it is not a shock that we are seeing a resurgence of Gill Sans. Will it surpass Helvetica? Who knows. Most likely it will serve it’s purpose to act as a sign of hope that we are moving forward and then we will transition back to a Realist-style sans serif like Helvetica during the next High Period.

Bibilography:

http://typophile.com/node/30970

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humanist_sans-serif_typeface

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gill_Sans

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helvetica

http://www.linotype.com/798-12627/thegermanluminaries.html

http://www.linotype.com/798/typographyintheartnouveauperiod.html

http://www.tug.org/docs/html/fontfaq/cf_28.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Depression#Turning_point_and_recovery

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_Deco

http://bnmhistoryofdesign.blogspot.com/2012/10/bauhaus-and-helvetica.html

http://www.signweb.com/content/bauhaus#.Uk8Jr4ashWA

http://idsgn.org/posts/know-your-type-gill-sans/

http://athertonlin.blogspot.com/2011/04/gill-sans-meaning.html

http://www.edwardtufte.com/bboard/q-and-a-fetch-msg?msg_id=00009r

http://www.webdesignerdepot.com/2009/03/40-excellent-logos-created-with-helvetica/

http://www.helium.com/items/1336072-hippy-versus-yuppy

http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-3468303119.html

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.130.5486&rep=rep1&type=pdf

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strauss–Howe_generational_theory

http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/baby-boomers-are-killing-themselves-at-an-alarming-rate-begging-question-why/2013/06/03/d98acc7a-c41f-11e2-8c3b-0b5e9247e8ca_story.html

http://www.pbs.org/wnet/need-to-know/culture/boomtown-the-great-suburban-demographic-shift/6808/

http://www.faqs.org/childhood/Ar-Bo/Baby-Boom-Generation.html

http://www.seniorcorrespondent.com/articles/2012/07/24/the-good-ol-days.452626

This is an excellent piece. I wish there was more written about typographic trends in culture. I’m particularly interested in two related trends.

1/ the return to serif typefaces for technology brands. When Apple created Mac in 1984 they zigged when everybody zagged by using Garamond as the signature type for a revolutionary new computer. When Jobs came back in 1998 he ditched that look and went full sans. Now, however, Apple and other tech brands are showing interest in more human fonts with lovely serifs. Why?

2/ I’d love to learn the cultural roots of the hipster branding trend, particularly in the use of type. Block letters and faux woodtypes are ubiquitous. Why is this rustic old school look coming back in the most creative subcultures of our country.

You can learn a lot about culture from type! Thanks for the great piece.

Larry, interesting questions – On the hipster branding trend: I’d refer you to the great British show “Yes, Prime Minister.” Said PM is planning a party political broadcast and asking for advice on the staging. Advice comes:

If you’re full of new ideas, you’ll need the oak panelling, roaring fire and a dark blue suit. On the other hand, if you have nothing much new to add right now, it’s modern art, high energy furniture and a light grey suit…

Modern Hipsters are a quintessentially urban culture…

The tech brands are “going human” because their products are perhaps asking us more than ever to adapt to technology? Of course it’s more complicated than this, there are other waves at work – see my short comment on the winning essay below.

In the spirit of CPS I have to applaud Carlen and then say… Yes, AND…

I think there’s another cycle at work as well, which is the cycle of over-exposure. Helvetica became commonplace in the world of new media and grassroots creation – partly because people could borrow it’s credibility and partly because it was one of a limited number of easily available technological options in the new tools.

Helvetica’s decline comes in part as tools for better font handling finally arrive.

So what does this minor chapter in the larger story of Helvetica suggest for Gill Sans? Well, if you believe Douglas Rushkoff (I don’t, but that’s for another day) then Gill will never reach the heights of Helvetica, because it will be over-exposed all the quicker. And then we’ll be on to something new – which matches the techno-story of the new Google font set…