To colonize the world, the Chez Panisse idea would have to go up against the Morton’s and Capital Grills of the world. It would have to unseat steak and potatoes. What was Waters’ business model beyond exotic recipes, eccentric ingredients and a really weird supply chain? (Chez Panisse actually sourced its goat cheese from hippies!) This restaurant in Berkeley was perhaps a little too Berkeley, a place fit for oddballs, aesthetes and gourmands of exactly the kind you would expect to find in the place that gave us the Free Speech Movement and a routinely disappointing football team.

Jobs in a sense was worse. Computers were more industrial than restaurants, but, if any thing, Steve was even less practical than Alice. He seemed more interested in creative applications than business ones. Sure, designers would like Apple computers. But if you wanted to do “real work” in the “real world,” you wanted something dead practical and this meant buying from someone like Bill Gates, who, whew, didn’t appear to have a creative bone in his body. Rumor had it that Jobs spend days agonizing over the color and shape of the case for the Apple II.[i] For Gates and his customers, any beige box would do.

The real trouble? It was all about them. Chez Panisse and Apple I were personal expressions of the creativity of Alice Waters and Steve Jobs. They did not rest until they made things just the way they liked them. Consumers, who cared about consumers? Alice and Steve were in the business of pleasing Alice and Steve.

Most business people accepted two things. 1. Close enough was good enough. The idea was not to be perfect, but to be better than the competition and to last one day longer than the warranty. 2. The only opinion that mattered was the consumer’s.

Capitalism is ruled by a fear of “surplus to requirement.” Everything that was surplus to requirement had to go (or never start) because it added time getting to market and subtracted money from the bottom line. The company that made a product better than it needed to be was bound to provoke shareholders to say, “Hey, stop giving away my earnings!” Engineering would break this rule, doubling the steel used to make a bridge, but this was a professional scruple. They wanted to err on the safe side. The rest of the world was working the art of “good enough,” “close enough,” and “that should do it.” Not because they were sloppy or lazy, but because this was pretty close to being the first rule of business.

The second rule of business is that the only person who really matters is the consumer. A business might have the best technology or the best product. It might be the best corporation. But unless the consumer bought what it was selling, too bad. In the words of Charles Coolidge Parlin in 1912, the consumer was king.[ii]

It took much of the 20th century to realize Parlin’s idea. Even late into the 20th century capitalism was still adding and refining techniques to make the consumer king. Information processing, focus groups, marketing science, psychology, anthropology, ethnography, design thinking, empathy, neuroscience, were all pressed into service. There was scarcely a theory or a method that wasn’t interrogated by marketers to find out who the consumer was and what he or she wanted.

Steve Jobs and Alice Waters broke both these rules. For them, “close enough” was an abomination. Jobs would go on tirades at Apple when his engineers delivered work that was merely good enough. He rejected the layout of the circuit board for the Apple II because the lines were not straight. This was, mark you, a part of the computer no one outside Apple would ever see.[iii]

Alice too was about the exquisite choice. In the words of Thomas McNamee, “She alone would dictate how every dish was to be prepared, down to the finest touch of technique: how brown a particular sauté should be, how many shallots to sweeten a sauce, how finely chopped. She knew exactly how she wanted everything to taste, to look, to smell, to feel.”[iv]

In a sense Jobs and Waters were at war with capitalism. They reversed the Copernican revolution. Capitalism was trying to make consumers the veritable sun (king) around whom everything else must turn. And Jobs and Waters said, “Wrong! Consumers aren’t at the center of things. We are.” And they hated the “good enough” principle, insisting on the exquisite choice.

Industrial capitalism was happiest when harnessing the productive powers of the machine, turning out enormous runs to create economies of scale, satisfying huge groups of consumers with goods good enough to please and prices both low enough to beat the competition and high enough to create value for the shareholder. All of this from an organization as faceless as a building with smoked glass.

Jobs and Waters had another idea: make very particular things, through the exercise of very particular choices, as created by highly visible individuals, driven by standards (and sometimes demons) that made the good better, vastly better, until it was in fact an exquisite choice. The consumer was now displaced as the arbiter of all things, and strangely, seemed to like this new arrangement just fine.

[i] Isaacson, Walter. 2011. Steve Jobs. New York: Simon & Schuster, p. 83.

[ii] Parlin, Charles Coolidge. 1912. Department Stores Lines. Philadelphia: Curtis. Bartels, Robert. 1976. The History of Marketing Thought. Columbus, Ohio: Grid Inc.

[iii] Isaacson, Walter. 2011. Steve Jobs. New York: Simon & Schuster, p. 74.

[iv] McNamee, Thomas. 2008. Alice Waters and Chez Panisse. Penguin, Location 827.

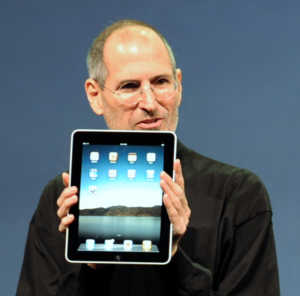

Image of Steve Jobs, courtesy of Matt Buchanan, with thanks to Flickr and Wikipedia

Image of Alice Waters, courtesy of David Sifrey, with thanks to Flickr and Wikipedia

To me, the issue is how to tell when these folks are right and when their critics are right. We only hear about the successful folks but where is the discussion of the the proven failures?

Jobs turns out to have been right but it took many years to prove out. Wasn’t he pushed out of Apple at one time before for these very traits?

UB, good point, history is written about the heroes, it’s a huge bet, with a huge pay off for the winner while obscurity awaits the loser. but I like this evolutionary model, lots of people trying and taking this big risk. as long as obscurity is the worst they suffer (and not poverty) and as long as the intrinsic rewards are enough for them, emotionally and er spiritually, then everyone’s well served. Thanks! Grant