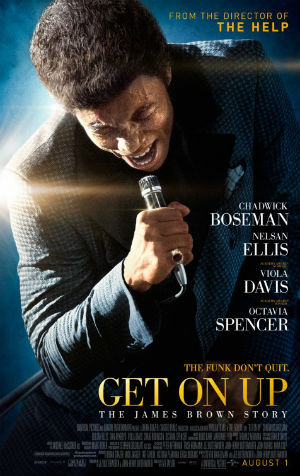

Richard Corliss describes Chadwick Boseman’s performance as James Brown in Get On Up as something that “radiates sex, drive, menace and spirit.”

Richard Corliss describes Chadwick Boseman’s performance as James Brown in Get On Up as something that “radiates sex, drive, menace and spirit.”

Oh, I thought, that’s kinda new. Normally, a series like this (“sex, drive, menace and spirit”) would have a little more redundancy. The “word herd” repeated itself to aid comprehension. In effect, the terms in the word herd meant roughly the same thing.

Words in the herd might even be near or actual synonyms. Thus the performance might be said to be “deft, subtle, nuanced.” The first term sets up the meaning, the last one spikes it. (To use a volleyball metaphor.)

But these days it is much more likely to see word herds that are diverse, with meanings working not together but happily in opposition. Each word does it’s own work. These word herds are heterogeneous. If terms used to be synonyms, now they are a little closer to antonyms. And the pleasure of reading comes less from going “Oh, that’s what she means. Got it.” to having to read the whole thing through, admiring the bumper-car effect of unruly language. Good writers aim for whip lash.

The methodological question: could we examine a large body of texts and see if indeed word herds are changing? The tricky part, I’m guessing, picking word herds out of millions of words of text. If this problem can be solved, then the question is whether there is some technique for judging the semantic distance between terms. What we are looking for, for the sake of this suspicion, is a “before” with relatively little distance and an “after” with lots of it.

Not to rush things, but I think there probably confirmation is waiting to happen. And not to really rush things, but my guess is that word herds are more heterogeneous for the same reason that so many things in our culture are more heterogeneous.

If once we were monolithic as a social and a cultural order, now we are various. And we are learning to live with this variousness. Homogeneous word herd are really training wheels of a kind. They were designed help us grasp the meaning of a text. And now they feel like a tedium tax the author is forcing upon us, as an unreasonable condition of entry.

It does feel like everyone is getting smarter. Certainly, and against the odds, popular culture is getting smarter and this lifts all boats. But the reason might be there in the everyday act of thinking. There was a time when we staggered beneath a weight of unanswered questions. Yes, we could go to the library and find an encyclopedia, but, Dude, really? All that indeterminacy created, to shift my metaphor, a film, a gauze. Meaning was hard to see. Distinctions hard to make. So it was left to the author to make everything clear, definite and precise. Got it?

Got it??? How laborious. Now that we can answer almost any question almost instantaneously, some of that film is gone. The world is windexed. The homogeneous word herd just feels like we are being struck about the head and shoulders by a schoolmaster who resents the fact that we are more interested in stray and playful meanings than his lesson plan. This is language acting like genre, setting up meaning over and over again to remove all doubt…in the process removing all surprise. We don’t need training wheels. Not any more.

This is a question for people with methodological skills I do not have. Maybe Tom Anderson might care to have a look. Or perhaps Russ Bernard might have a student who cares to take this on. Please, if you have a way of solving this problem, sing out!