There’s a small trend in the works. People are daring to recast popular shows on TV. In the image above, Entertainment Weekly dares imagine the new detectives for True Detective. Here Ryan Gosling and Denzel Washington are proposed as replacements for Woody Harrelson and Matthew McConaughey. (Apparently, HBO and or Nic Pizzolatto had always planned a modular approach for the starring roles.)

Digital Spy undertook the same recasting, proposing Ian McKellen and Patrick Stewart as the new True Detectives. This would count as irresistible TV, in an era of irresistible TV.

Grantland took the thing a step further, proposing a fantasy league for Hollywood.

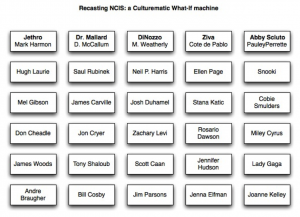

There is a quite wonderful book called Culturematic that suggests a way to recast NCIS.

The idea is everywhere. Ok, not everywhere, but this is a gusty little trend breezing its way through contemporary culture.

This shows a new order of participation in culture. It’s hard to imagine this sort of thing happening in the 1950s when people took what TV deigned to give them and were grateful for it too.

But people now new and deeper knowledge of popular culture and they are eager to use this knowledge. Exactly this sort of thing happened in the case of professional sports. The inventors of Fantasy Football believed that only sports journalists would want to participate. What they didn’t see was that sports fans had read so much sports journalism, that they too were itching and able to participate.

This relates I think to yesterday’s post on Pharrell’s Happy video where I suggested that crowd sourcing talent is not always successful. But here when we ask people to engage not as actors but as critics that the chances of success go up. Its as producers and directors that we are most interesting, productive, and engaging.

We should also observe the presumption at work here. One of the reasons that viewers in the 50s wouldn’t engage this way is that it was presumptuous to do so. Creative decisions were things made by experts in big cities, people and worlds away from their own.

But now we are, to use the Tudor phrase, “over mighty subjects.” We take for granted our right to second-guess creative decisions. Our knowledge of culture is not passive but active. This means that even as we consume culture, we expect to produce it. If only in our heads. If only in the conversation we have with friends and family. Anyone who finds a way to engage us in this way (we shall keep an eye on Grantland’s fantasy league) is creating value for us and value for themselves. (Thus do anthropology and economics intersect.)