Ethnography has grown in the last couple of decades from a moody, friendless method in the social sciences to the belle of the business ball.

But clearly it has suffered in this rise to stardom. In the wrong hands, ethnography is now a license for the methodologically slap dash. To use the immortal words of Errol Morris, ethnography is now sometimes “cheap, fast and out of control.”

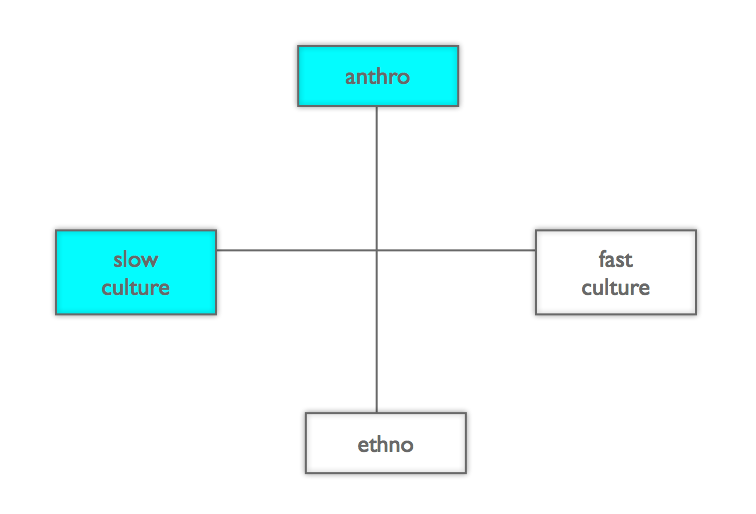

Part of the problem, I think, is that ethnography has been shorn away from anthropology. It was created by anthropologists (and to a lesser extent sociologists) and used in conjunction with anthropology (or sociology).

The advantage of adding “anthro” to “ethno” is that it allows us to put things captured in the life of consumer, user, or viewer in a larger, illuminating context. We can see, more surely, what it means. Without this larger context, ethnography devolves into simple observation, as in “this is what I saw when I was in a consumer’s home.”

Adding “anthro” to “ethno” also give us access to theoretical resources and intellectual traditions that contemporary ethnographers rarely seem to bring to bear on the problem at hand. (And I’m sure that I don’t need to say that the “problem at hand” for any ethnographer studying the ferocious dynamism of contemporary culture is usually formidable. We need any and all the powers of pattern recognition available to us. Airily dismissing the patterns made available by intellectual discipline and years of theoretical development is just dumb.)

How can we tell that someone is adding “anthro” to “ethno?” We are entitled to ask “where did you study anthropology?” (We could also use “sociology,” “film studies,” or “American culture.”) We are asking, “what do you bring to the table beside a claim to method?”

But this is only part of the problem. Too often, the researcher has no “depth of field.” He or she is incapable of seeing that this family, this home, the user, this community is a creature in motion changing in real change. Good observers have an acute sense of the historical factors at work here. They know what has happened in a very detailed way since World War II and they have a general sense of what has been happening in Western and especially American culture over the last 300 years.

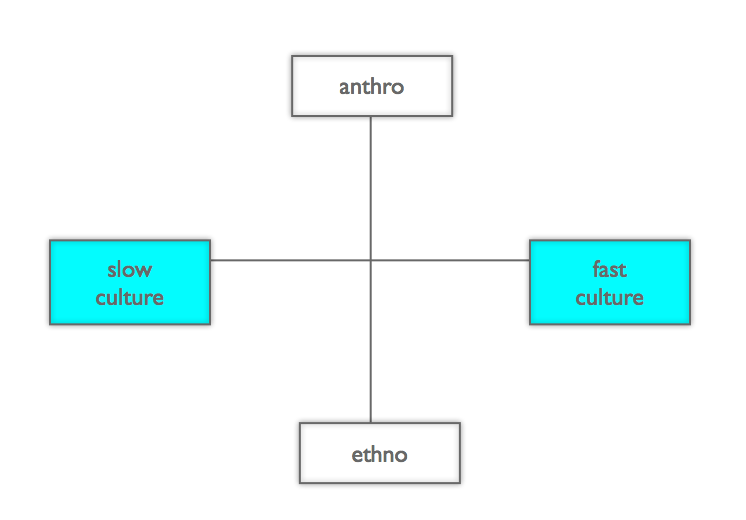

This gives us a glimpse of “slow culture” as well as “fast culture.” (For more on the distinction, see my Chief Culture Officer.) And now we are really testing the abilities of the self appointed ethnographer. Do they have depth of field? Now we are entitled to ask, “tell me about any big, enduring trend in American culture. How did it take shape over time?”) (Don’t be surprised if they are astonished by the question.)

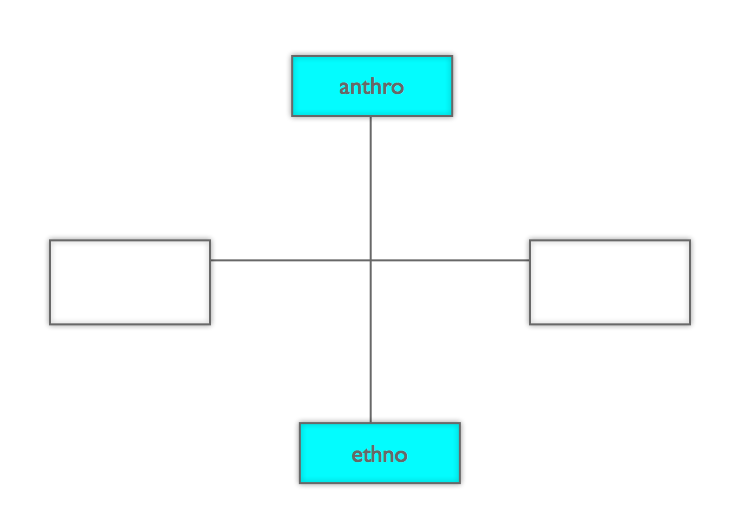

Here’s the problem. Most of the work being done by ethnographers is being done here.

But this ethnography is stripped of the things that gives it real explanatory power.

What we need is something that heads in this direction.

If ethnography is to evolve, we want to migrate in the direction of “anthro” + “slow culture.” We could think of this as a “Northwest passage” strategy. Until we find a way to connect these worlds, the Southeast sector must remain poorer and less cosmopolitan.

It’s not clear to me what the practical solution is. I did a couple of posts about the C-school idea a few years ago and discovered some of the following programs, any one (or several) of which might take up this challenge. (Notice that I am not saying these places have a solution, merely that they are the kind of places that might come up with one.)

The D school at Stanford (David Kelley)

W+K 12 (Wieden + Kennedy school, Victor a German Shepherd pointer)

The Miami Ad School (Ron & Pippa Seichrist)

The VCU BrandCenter (Helayne Spivak)

The Berlin School of Creative Leadership (Michael Conrad)

EPIC (Ken Anderson and Tracey Lovejoy)

UC Berkeley School of Information (AnnaLee Saxenian)

California College of the Arts

Royal College of Arts

MIT Media Lab

Rhode Island School of Design

IIT Institute of Design (Laura Forlano, thank you Sergio)

Ethnography Training (Norman Stolzoff and Donna Romeo)

Consortium of Practicing and Applied Anthropology

Ohio State (Liz Sanders)

University of North Texas

Wayne State

Columbia Business School (Bob Morais)

Fordham Business School (Timothy Malefyt)

Savannah College of Art and Design (Sarah Johnson and Susan Falls)

As I was noting here, the Annenberg School at USC is coming up fast.

Finally, I recently had lunch with John Curran and he tells me that things are afoot in London. I will leave it to him to reveal the details. (John, please send me a link so that I can include it here.)

I am hoping readers will let me know the programs I have missed.